Systems thinking is the study of how and why systems behave the way they do.

Government is arranged and funded in departments. I think it’s fair to say that over the past century, government hasn’t always considered the delivery of public services or the creation of policy in a ‘systems way’.

In some cases, working in a silo is the best way to get the job done, but evidence suggests that for more complex challenges it isn’t always.

From the outside it might look like too much of a challenge and disruption to the status quo.

Some people say that systems thinking is too technical, others say it’s not technical enough. Some people are mystified by it and don’t want to engage with it. Others want to but don’t know how to get started. I’ve become a bit of an evangelist. The approach might not be right for every challenge we face, but I didn’t want it to be the case that people didn't have an opportunity to learn about it.

I decided to hold a seminar for some of my team and some colleagues from the Government Office for Science. The seminar was a very light-touch introduction to one method of systems thinking. I must add that systems thinking is just one way of thinking about a complex challenge.

In this blog post, I want to share with you what I shared with them.

The Method

There are lots of ‘ways in’ to systems thinking, but I think that a good place to start is to use a context diagram. It comes from Dealing with Complexity: An Introduction to the Theory and Application of Systems Science by R.L Flood and E. R Carson.

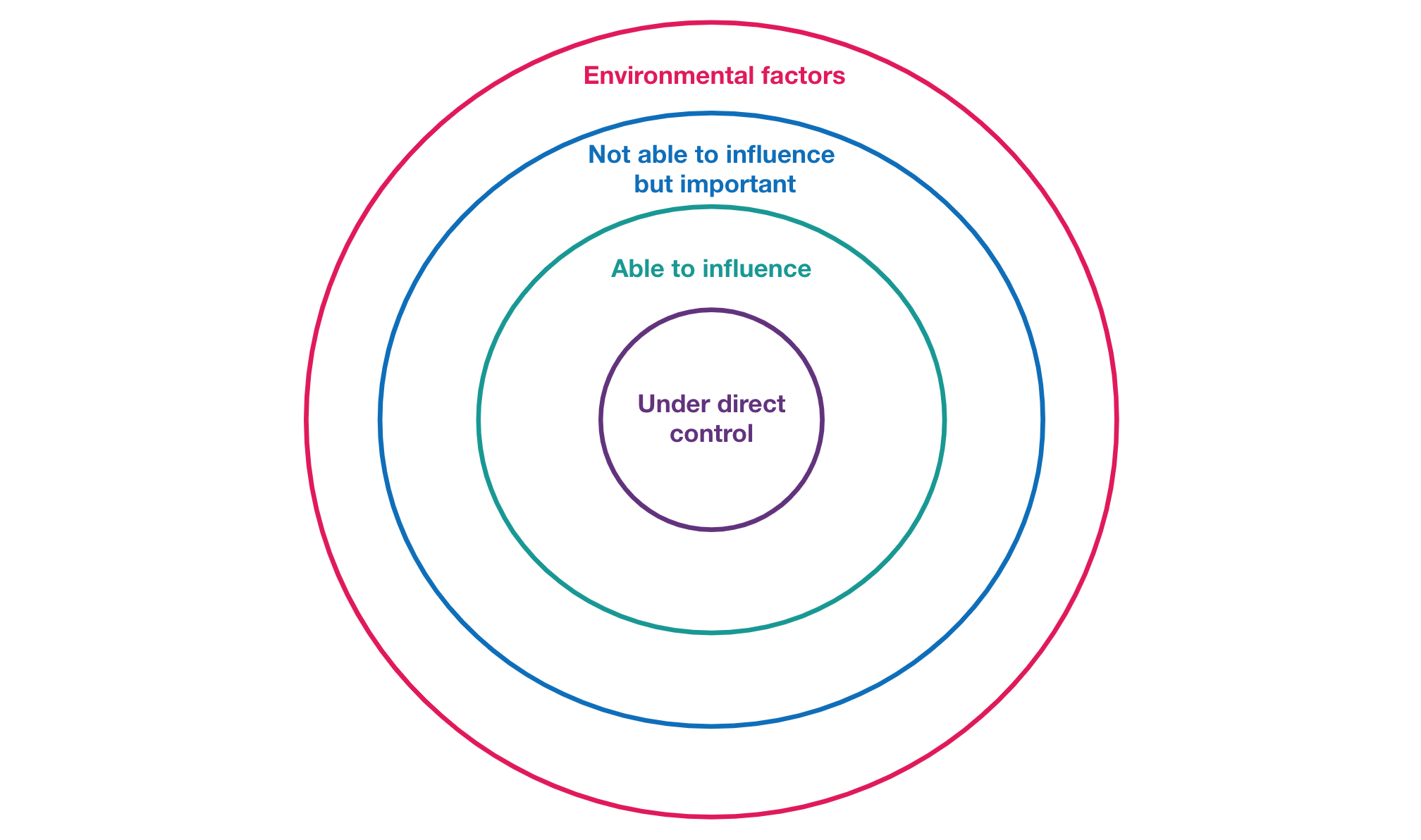

Using a context diagram, you start by stating the complex challenge in the middle.

My seminar was interactive so the complex challenge that I set for the group was ‘How do we embed the Strategic Framework successfully into Government?’

The group divided in two and began to fill in their context diagram, which is essentially a series of concentric circles. So, once you identify the challenge or system, you work outwards.

Inside the first ring you identify those elements of the system of interest, things that are under direct control. So in our case it included the Strategic Framework narrative and vision, the communications plan and our personal motivations to focus on our work.

Inside the second ring you identify the elements that are not under direct control but can be influenced. So for our teams that included the Spending Review, other departments, and so on.

Inside the third ring, you identify ‘local constraints’, things like local regulations over which you have no influence or control. Automation, parliament, the culture of working in silos.

In the final ring, you look at the wider environment over which you have absolutely no control. That might include the weather, alignment of the planets, world crisis.

What we learned

Populating the context diagram is a great group activity and systems thinking itself is a collaborative endeavour. It encourages a diverse range of perspectives and this exercise really demonstrated that. It also uncovers assumptions, which are important to interrogate.

Once we finished the exercise, we looked at the rings and summarised what we learned from the process. We agreed that it was a good way of unearthing and challenging some of the assumptions people hold. The process also helped us to surface implicit boundary judgements and assumptions.

It was a useful exercise to list stakeholders and to imagine how they might view their powers of influence in the system. It helps you compile a list of stakeholders in a thoughtful way. Someone drew a stakeholder grid on how to engage with people in a tailored way. In that way, it gives you a sense of priorities for engagement.

The feedback following the session was positive. It started at 4pm and ended at 5pm, but people stayed and chatted about what they’d learned for half an hour afterwards! I want the next session to be a lunchtime session so more people can attend.

Spreading the word

I hope that I'll be able to open up the seminars to a wider cross-government group.

However, there are opportunities to learn more about systems in the public sector. I went on a course on systems thinking which was held by the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) which is an agency of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and it was fantastic. Dstl opened up its course to me, which is a great example of systems thinking practitioners working in a collaborative way.

The SCiO website is worth checking out, too. This is a community for professional ST practice.

The Systems Thinking Interest Group runs SysTime - which is a practice of a method every few months. The next SysTime is due to take place in Leeds, and they are planning to run a parallel session in London.

If you have any other resources to share, please comment below.

My advice for thinking in a systems way:

- Resist the urge to arrive at a quick conclusion or solution.

- Focus on assumptions and mental models.

- Systems thinking is as much about the means (creating group understanding) as the ends (seeing the big picture)

14 comments

Comment by David Buck posted on

I'm getting caught up in the semantics around this 'the wider environment over which you have absolutely no control.' I would agree that you can't control a system, but I also think you can impact on the wider environment and for me impact and control are closely linked. I can't impact on the weather of today but I can impact on the weather of future years (tomorrow).

Comment by Ian Glossop posted on

Good Stuff.

Nice to see Flood and Carson being referenced.

You might want to introduce the "Formal System Model" as a means/method of analysis as the next step in getting into "Systems Thinking".

https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/systems-thinking-complexity/0/steps/20390

Comment by Geoff posted on

Systems thinking is NOT simply about the study of systems and how they behave. This is a miss understanding. There is a very difference between thinking about systems and thinking in system. Your statement implies systems exist as tangible entities. This is not always true or correct. Good engineering, for example, starts with a conceptual systems map/model. This does mean this exist as a physical entity. See openlearn from the OU for the basic ideas and concepts which have taught for the past 50 years.

Comment by Ian Glossop posted on

You may - or may not - be correct about the difference between thinking in systems and thinking about systems. But at the introductory stage the distinction is unimportant. Better to get people thinking about systems - tangible or not - through practice in applying systems concepts before exploring the nuances in the theory and philosophy. I don't think anyone looking at systems in Government - or the wider public sector - will assume that systems are tangible things - most of the ones they look at will not be. Getting into subtle philosophical differences will only make it seem academic and irrelevant to the real world of public service delivery. [Which is not the message we want to give people.]

Comment by James Hostford posted on

Thanks for reading my blog post Ian, and thanks for the recommendation.

Comment by James Hostford posted on

Hi Geoff, thanks for taking the time to read my post. I agree that complex systems are, by nature, intangible and full of unknowns. I wrote this blog with a general audience in mind to show what I'm doing to introduce systems thinking into policy-making.

Comment by geoff elliott posted on

Hi James, systems thinking into policy-making. I would argue there are two major challenges, One, systems integration at a policy level. And, two, policy cascade to an operational level. If you like, in VSM terms, S5 to S1 including managing the dynamic feedback loops.

Comment by Kees van Haperen posted on

I absolutely agree with Geoff's comments! The starting point is the fact that we have to deal with complexity or messy or wicked problematic situations for which we use 'systems' as a concept to help us explore them. In such cases which involve people and which are known as 'soft', 'systems' do not exist in the real world but help us to make sense and learn (see Brian Wilson, Peter Checkland).

Comment by Geoff posted on

Hi Kees, one additional problem is that many people, particularly in the public sector for many reasons don't understand the language of systems thinking. Unfortunately their comfort zone tends to around the use of structured methods, eg, DMAIC and PDCA as these are seen to be risk free and solution focussed.

Comment by David Adams posted on

Good stuff.

'Where to start?' is always a challenge, particularly if you've got a mixed audience + for a very short period of time. Regardless of methods and terminology, just by getting a group of people to start framing a shared problem differently you can at least generate curiosity.

Hope this is the start of something productive...

Comment by Benjamin Taylor posted on

Really interesting, and a great way in to the subject.

Other ways we use are forcing people into metaphor and multiple perspective, and case studies and real-life examples - after all, systems/complexity/cybernetics is practically focused; it's about finding more effective ways to act in context.

I haven't got that book (which surprised me!) but there are many useful models out there looking at cascading levels of containing system (physical and/or levels of logic). What you did reminds me of these, and of Covey's circle of influence and circle of concern - and, to an extent, of my own original exercise 'breaking the shell', where levels of control and influence are used to help shift psychology to successfully accomplish a task (and plan, manage risk, generate real learning, and raise issues) - you can see that here: https://www.dropbox.com/s/eyqdmxuqxpv7863/Breaking%20the%20Shell.zip?dl=0

However, the one thing that concerns me a bit is the potential conflation of systems 'levels' (a hierarchy of physical scope and/or conceptual levels) with levels of control. I'm not sure that's helpful, because it's not true, and constraining. The example as given is strictly focused on levels of potential control but the potential for confusion is evident.

To take a really weird but vivid example, in most situations there is a 'nuclear option' - literally, in the case of countries involved in armed conflict. This kind of option would completely reshape the environment, but might be as much within 'local control' as the simple press of a button...

You know by now that what you will get with systems thinking is lots of people (and mostly older, well educated, white men, we should note) giving all kinds of advice, quibbles etc - I agree with other commentators that this fact of systems thinking life must not be allowed to put everyone off!

Comment by Rachel posted on

I work on the ground (literally!) so think of myself as being at the at the "delivery end" of policy. There are silos throughout organisational structures, and I feel it's important to build mutual understanding to keep policy realistic and delivery dynamic. I am Interested in finding efficient feedback loops to connect policy and practice so would be grateful to hear about any future (online) seminars you run please.

Comment by James Hostford posted on

Hi Rachel, thanks for reading my post! It would be great to learn more about your experiences and I can connect you with future opportunities if you email systems@cabinetoffice.gov.uk

Comment by Nicholas Oatley posted on

If you start with the definition of a system as being "A set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its “function” or “purpose.” (Meadwos D) you might want to begin exploring the dynamics that maintain the system you are focusing on in order that you might disrupt the dynamics and move it towards a healthier state (or to achieve the state that you want the system to move to). To do this you will need to map the system using causal loop diagramming and identify leverage points to disrupt the system (amplifying bright spots and reinforcing positive energy in the system where that exists, or mitigating or reducing the effects of negative forces in the system). Here is a great how to guide to do causal loop system mapping https://docs.kumu.io/content/Workbook-012617.pdf

Nick Oatley Senior Adviser, The Global Knowledge Initiative