‘Collaborate’ has become something of a rallying cry in the public sector over the past few years. We’ve heard how collaboration leads to better outcomes for citizens, how it has enabled civil servants to better spot (and avoid) unnecessary duplication and how it can improve morale. All good things.

However, when it comes to designing systemic policy solutions to complex problems, I believe that collaboration, on its own, is not enough. So what is needed beyond collaboration? I thought I’d share my thoughts in a blog post and share three concepts that might help you engage with stakeholders on the topic.

Be collaborative, but think systemically

Firstly, I want to say that systems thinking and collaboration aren’t the same thing. Many may think that by collaborating, they’re approaching things systemically. They most likely aren’t. In order to develop systemic solutions yes, you need to collaborate and convene systemically, but you also need to ensure stakeholders are thinking systemically.

Bringing stakeholders together is absolutely essential if you want stakeholders to better understand a system, define their goals and design a solution.

Collaboration means stakeholders have an opportunity to be heard. The system benefits from diversity of thought. It can also help people to resolve conflicting views and potentially reach consensus.

But it’s just as important that there is a change in mindset towards thinking systemically because even when stakeholders convene, there is a high risk they assume that the best way to improve the system is to focus on their individual part.

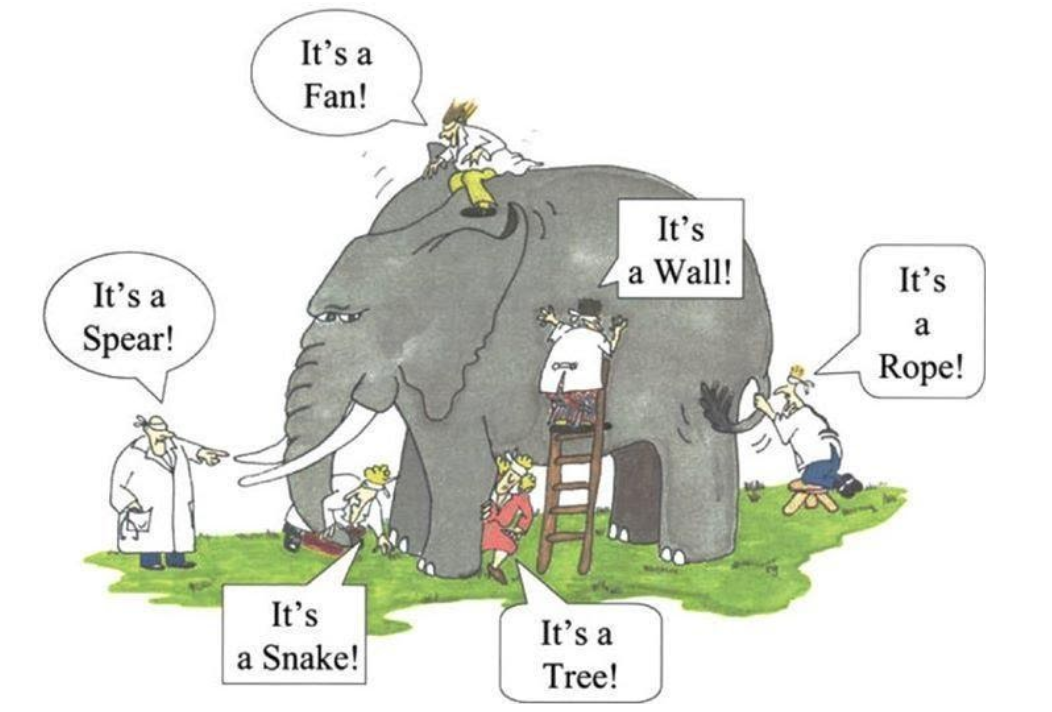

Consider the elephant

One way to help ‘think systemically’ is to consider the elephant.

You might be familiar with the ancient parable of the blind men and the elephant. In the story, several blind men interact with a different part of the same elephant, assuming that what they are interacting with is the whole elephant.

They do not see that they are interacting with one piece of something bigger and more complex.

For me, it illustrates the challenge of enabling diverse stakeholders to see the bigger picture.

To optimise the performance of the entire system, stakeholders need to shift from trying to optimise their element of the system to improving relationships among its constituent elements. They need to shift towards thinking systemically.

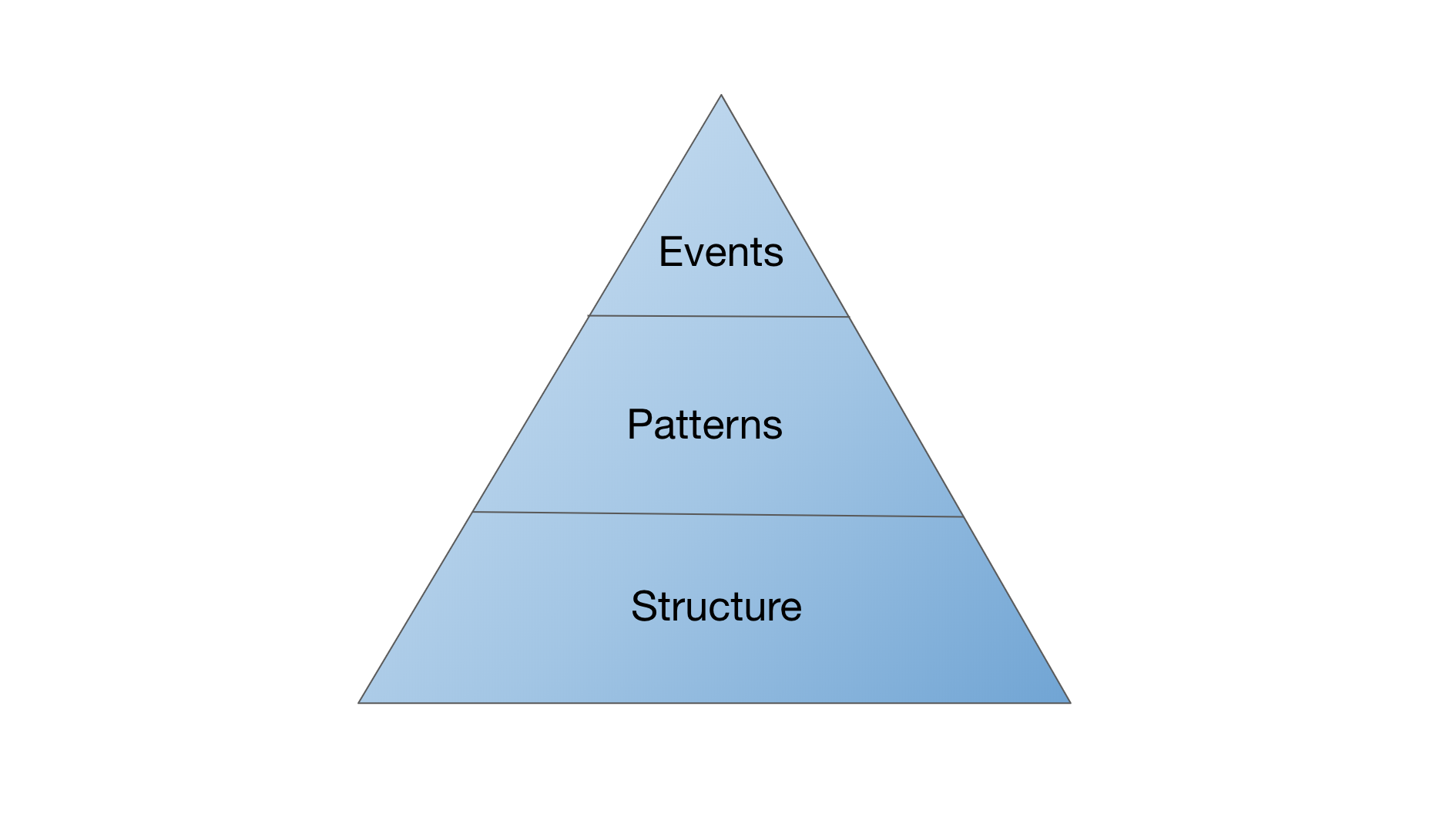

Use the iceberg

Another concept for helping stakeholders develop an initial picture of the true elephant (any complex system) and beginning to look at things systemically, is the iceberg metaphor.

It is a simple means of distinguishing problem symptoms from root causes.

The iceberg distinguishes:

- Events (what happened)

- Patterns of behaviours that link events over time (what has been happening)

- System Structure the hidden element of the iceberg that causes the most damage because it shapes the trends and events (why has it been happening)

The root causes of a chronic, complex problem can be found in its underlying systems structure – the many circular, interdependent and sometimes time-delayed relationships among its parts.

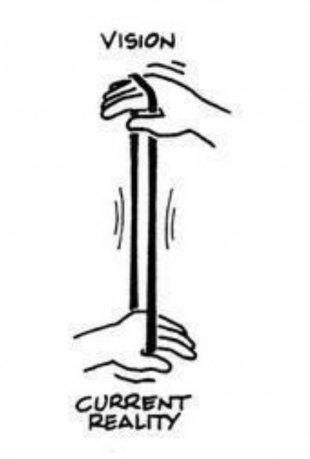

Creative tension

A concept which can help resolve a complex problem is that of a ‘creative tension’ model introduced by Peter Senge in ‘The Fifth Discipline’.

This proposes that the energy for change is mobilised by establishing a discrepancy between what people want (a goal or vision) and where they are (current reality).

Source: The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge

When stakeholders have a common goal and a shared understanding of not only where they are now but also why – they can then establish a creative tension, which they are more likely to be drawn to resolve in favour of their goals.

Stakeholders often agree on where they are at the top of the iceberg, but fail to see the underlying systems structure that they are affecting and affected by. Developing a shared understanding of why the current reality exists, using something like a systems map, is essential to addressing this visible challenge.

Developing a shared picture of what people want as well as of reality at a deep level enables stakeholders to experience their responsibility for the whole system not just their own role.

The top and the bottom of systems thinking and collaborating

When developing robust solutions to systemic issues, stakeholders need to, in addition to collaborating, start thinking systemically and make 3 broad changes:

- from observing their own area to seeing the wider context, and considering it as a system

- from hoping others will change to seeing how they can first change their own actions and behaviors, and shift how they relate to others in the system

- from concentrating on individual events to understanding and redesigning the deeper system structures that cause these events

In helping stakeholders along this journey, you might want to consider sharing the concepts of the elephant, the iceberg and ‘creative tension’.

Do you agree? Disagree? Have any other concepts to recommend? Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

21 comments

Comment by john mortimer posted on

Yes, your account sounds very familiar to me.

In my experience, the actions defined by the term Collaboration are quite useless unless they are underpinned by understanding how and why the service has been designed that way. If the why changes, then there is hope that the what changes. Then collaboration will be an outcome in many cases.

Your point about taking stakeholders with you demonstrates that fundamental shifts in perspective, and understanding their service as a system is key. Certainly, if this is not undertaken then any change will not be real and sustained, as it will only affect part of the system.

Comment by Geoff posted on

You cannot hold a conversation if you don't speak the same language. Systemic thinking is being confused and contaminated by process thinking particularly in the public sector. Unfortunately many do not understand the concepts and ideas underpining system thinking

Comment by Sam posted on

Would you be willing to share any of the concepts and ideas underpinning system thinking?

Comment by Geoff posted on

Hi Sam, yes, what is the most appropriate mechanism. ST covers a wide continuum where on the one hand people dominate a problematic situation and its setting. Too, on the hand things dominate. ST can be thought of as 4 things.

1 the major writers

2 underpinning con pets and ideas, there are about 20 or s

3 Approaches. There is about w0 different approaches, eg, SSM, VSM, CSH, CHAT, SD, SE, AI

4 sensemaking diagramming methods.

Comment by Sam posted on

Thank you Geoff.

I'm most interested in 2) the underpinning concepts and ideas.

Comment by Geoff posted on

Hi Sam, some of concepts include but are not limited to are

Open and closed systems

Emergence

Entropy emergence

Relationships

Multiple perspectives see lindstone mitroff

Parts and wholes

Boundary critique

Holism see Smutts

Terminal ends

Ashby law of Requsite variety

System of interest

System in focus

Recursion

Feedback loops

Ashbys regulator model

See also Clemsons systems laws

Hope this helps

Plus clean language

Surface and deep language

Metphors

Ashby survival space

Comment by Marcin posted on

Can you please decipher the shortcuts?

1. SSM – Soft System Methodology

2. VSM – Viable System Model

3. CSH – Critical System Heuristics

4. CHAT - ?

5. SD – System Dynamics

6. SE - ?

7. AI – Artificial Intelligence

Comment by Sam posted on

Thank you Geoff - that is helpful

Comment by geoff elliott posted on

CHAT - Cultural History

5. SD – System Dynamics

6. SE - Systems Engineering - INCOSE

7. AI – Appreciative Inquiry

Comment by Chris Sheader posted on

Totally agree Geoff - root cause is deterministic/mechanistic, whereas complexity understands there is no single root cause. Any condition, or emergence, arises from the interaction of myriad characteristics.

I have come across, sadly, a number of proponents of 'systems thinking' who do not understand complex adaptive systems to a meaningful level - this can be very dangerous indeed.

One key takeaway from complexity 'sciences', at least for me, is that template approaches do not work - the chaos theorists talk about the 'sensitivity to initial conditions'. I would urge anyone, especially in the current environment to understand at least this point when considering action, and lways act contingently.

Comment by Chris posted on

Thank you for making these very important points. The system mindset is a prerequisite for transforming a complex civic system (housing, food security, health economic development, etc.) Too often collaboration is seen as the solution, rather than a tool. Collaboration is often required to implement technical solutions, but such solutions don't result in transformation. We need to help people first understand the civic system they want to change, before they can collaborate to transform it.

Comment by Jelel Ezzine posted on

This is the key issue. When apprehending a complex situation and dealing with stakeholders with no background in ST, having them involved is far from being easy nor useful. There must be an initiation phase to ST before engaging the stastakeholders.

Comment by JG posted on

Having good outcome measures can help too. Or good proxies instead, eg the closure of Waffle House restaurants in the states are a good indicator of the severity of the Covid-19 crisis.

Comment by Adam Jones posted on

I agree. Having a clear sense of the outcomes you are trying to achieve, as part of the creative tension model, and longer term measuring your progress on delivering to these outcomes (once you've developed robust policy interventions) is absolutely critical.

Comment by Peter posted on

I really enjoyed this blog, thank you. the one concept I might add to the list is starting collaborative systems work by scenario planning with diverse groups of systems stakeholders. I think that pre-work to co-create alternative plausible scenarios would make subsequent systems design work more robust. The work of the Oxford Scenarios Planning Approach is interesting in this regard https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/oxford-answers/oxford-scenario-planning-approach-era-covid-19

Comment by Adam Jones posted on

Yes I agree Peter that scenario planning can be a really critical part of systems thinking (although concept/tool overload is something I think is something to be conscious of). It can help stakeholders focus on the desired outcomes/futures for the system and in some instances avoid the risks of group think by exploring 'what if' scenarios.

I wasn't aware of the Oxford Scenarios Planning Approach work, so I will absolutely check this out.

Comment by Rachel posted on

I probably do my colleagues' heads in with my keen interest to find the devil in the detail, but my personal view is - if you can't see all the detail, how do you know how big the picture is?

I'm not familiar with management theory, but to me it seems that any approach to engaging with stakeholders needs to be able to function for stakeholders as people. Individuals. As we all are. With our personal and cohort perspective, agenda and expectations. These are what drive a stakeholder to engage. And what sets the level of energy and commitment they participate with. So if round pegs fit in round holes...what is gained by shaving off the edges so they fit together more neatly? Circles might not tessellate but they can be linked to form strong chains.

So, to labour the blind men and elephant metaphor you used....

If a room's got an elephant in it, even a sighted person might not be able to conceive it as a whole, especially if the room is also filled with other people. When people are put into a space with strangers or adversaries, I notice that they tend to drift towards the familiar. So, on encountering a space (be that physical or political) crowded with an elephant and other stakeholders, a person is most likely to focus on the part of the elephant they are familiar with so they can remain comfortable and confident.

And if that part is their strength, does it always matter whether they can see the whole elephant? So long as they know it's there? And have a vague sense that the part they're interested in belongs to something quite big. And perhaps what direction it's going in. And how the part they are particularly interested in can influence or is affected by that.

Each stakeholder has only entered the room with the big elephant because they want to convey knowledge about the part they're interested in, so the room needs to hold enough people to ensure the functioning of each elephant part (inside and out) is understood. And if the stakeholders don't speak the same language, someone needs to be able to translate without loosing meaning. Otherwise the consequences of change in one part on another part might be overlooked.

Sometimes the stakeholders will make the connections between each other just because they are interested in the same elephant (even if they don't agree on how to describe an elephant). Sometimes they won't. Because they're people. We're people. Sometimes we don't ask the right questions. Sometimes we don't listen to the right answers.

So, in my opinion, in an effective system, a stakeholder doesn't need to be able to sketch the whole elephant...their value is the imagination and detailed knowledge they bring to optimising part of the elephant. The purpose of the system is to identify potential impacts and create flow between constituent parts so that the overall achievement can be optimised. To do this, the system needs ways of determining whether a change in one part causes a favourable or unfavourable overall outcome. So it's important that the creator of the system builds in ways of learning what are critical thresholds of change in the elephant.

Which is what evolution has been doing for quite a long time now...resulting in extinctions and divergences in response to a situation. So I don's suppose there's any point in kidding ourselves that we will find the perfect solution to life's challenges, but worth plodding away 'till we develop something slightly less peculiar looking (and less attractive to poachers!) than an elephant!?!

Comment by Adam Jones posted on

Hi Rachel, thanks for your comments.

We absolutely want to draw on the expertise of individuals, especially when they understand their part of the elephant so well. You ask 'does it matter whether they can see the whole elephant so long as they know it is there?' - I would agree that acknowledging the rest of the elephant exists is a gigantic leap from thinking the element you focus on (and work with) is the whole picture. This is a leap we really want people to make.

You mention the value of ' determining whether a change in one part [of the system] causes a favourable or unfavourable overall outcome' - I agree and would suggest that conducting exercises such as systems mapping can aid the development of policy and strategy that is more likely to avoid unintended consequences in the system of relevance. There are no guarantees of perfection here, only increased likelihood of success towards desirable outcomes.

You also mention 'creator' of the system, in my opinion the 'creator' of the system is actually all the constituent parts combining to create the system structure (essentially stakeholders and their actions) and that is why it is important we convene systemically.

I'm not quite sure what extinction means in your extended metaphor, but ultimately we should be looking to design systems that produce the behaviour we ultimately want to see and that means working out and agreeing a vision for the system.

Comment by Adam Jones posted on

Regarding the benefits of parts of the system understanding the other parts, I would recommend reading up on the 'Beer Game', which Peter Senge talks about in chapter 3 of 'the Fifth Discipline'.

https://readingraphics.com/understanding-systems-thinking-the-beer-game/

Comment by Trilly Chatterjee posted on

Hi Adam. I'm Practice Lead for Product Management at NHS Digital. Really interested to learn more both about the Systems Unit, and the System Thinking Interest Group. Would be great to work out how we can discuss further.

Would also be very interested in your perspective on Paul Pangaro's work - a small (highly relevant) excerpt here.

https://vimeo.com/189864748

Comment by Adam Johns posted on

A really good systems thinking primer, Adam. I'm keen to hear more of your thoughts on "root cause" in complex systems. In safety science, root cause - and causation more generally - has been largely debunked. It's described as a social construct, that is to say we construct causes after the fact once we have all the data from an event. Root causes suggest some cause-effect linearity in the development of an event, and that they can be found be retracing one's steps. Complexity science tells us this can't be true. Systems thinking also includes the principle of Equivalence, so a 'bad event' can't stem from a 'bad cause', since all outcomes generally stem from the same path, just with subtly different conditions.

See more here:

https://www.verica.io/inhumanity-of-root-cause-analysis/